2026-01-31 | [misc]

It may be more than a month past Christmas, but this is something that's been in my "get to it whenever" box for a while.

These are "Caroling Christmas Bells" made by "Capricorn Electronics". It consists of a plastic control box and twelve inexpensive tuned bells. Inside each one is a small coil (which looks suspiciously like it was taken from a cheap relay) which hits a clapper against the side of the bell, playing the note. It is quite old; you don't really see things like this nowadays since even cheap electronics can drive a speaker with either a decent quality synth or a full recording if you wanted to make a music box.

These kits are still out there - you can find videos of them like this one.

The bells are on two reasonably long strands of wire, perhaps so you can hang them in a tree. I 3D printed some clips to attach them to a pole, for easier handling.

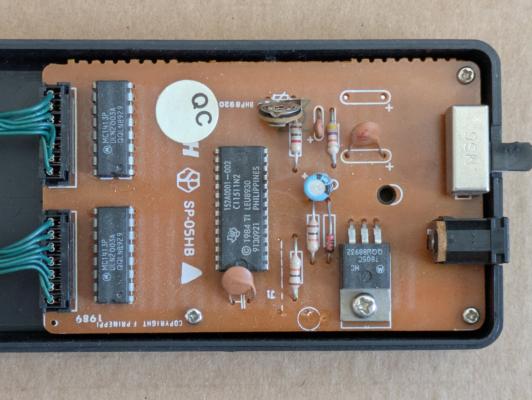

On the PCB, there are only 4 ICs: a 5V regulator, an unknown microcontroller/sequencer IC, and two open-collector transistor arrays for driving the bells.

The potentiometer changes the speed of playback. The bells have little damping, so it's better to keep it slower.

Search up the name "F Prineppi" as silkscreened on the PCB and you'll find a large list of patents, many of which relate to decorations and Christmas Lights. However, the patent for these bells is not one I found among them. The case does say "patent pending" so perhaps this one was not granted?

Date codes on the chips suggest 1989, which seems about right when you go searching for these bells.

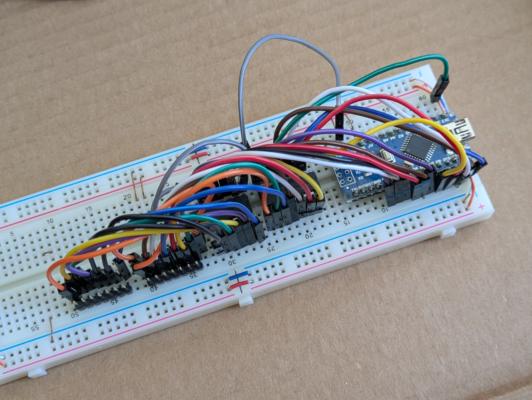

The transistor array chips make it obvious how to drive the bells from another source. One pin on each strand is for +12V, and you connect the other pins to GND with a transistor. I tried 2x ULN2003A and an Arduino and it works just fine.

However, the bells are a pretty limited way to play MIDI files, because they are only 12 of them, and they don't cover a full chromatic scale. The notes are:

0: 329.63*2, # E5

1: 293.66*2, # D5

2: 261.63*2, # C5

3: 246.94*2, # B4

4: 233.08*2, # A#4 / Bb4

5: 220.00*2, # A4

6: 196.00*2, # G4

7: 185.00*2, # F#4 / Gb4

8: 174.61*2, # F4

9: 164.81*2, # E4

10: 146.83*2, # D4

11: 130.81*2, # C4

It reminds me of my thoughts about replacing the drums of cheap wind-up music boxes with 3D printed versions to make your own song. Usually, they just pick the notes they will need for the song and make a special comb just for those notes.

Because there are open collectors on the original board, you can also hook up the original board to a microcontroller directly (I used the same Arduino with pullup resistors) and log the entire note sequence. Is this even worth doing? Probably not, but I did it.

The arduino constantly spits out strings like "000000001000", with a 1 if the note is on, and a 0 if the note is off. I logged it with a python program, then condensed the log with wait times between note changes instead of the full log. It ends up looking something like this:

...

0017643 000000001000

0017666 000000000000

0017816 000000100100

0017839 000000000000

0017984 000001000000

0018012 000000000000

0018157 000010000000

0018180 000000000000

0018330 001000000000

0018353 000000000000

0018497 010000000010

0018526 000000000000

...

with the left column as the timestamp, and the right colum as the notes to play.

Ok. I don't know much about sound in the browser, so I'll have to rely on ChatGPT to make me a player.

Something that stands out to me is the quantization of note events to the nearest 16th note, which give the sequence a very rigid feel. Still, that's about a half-hour of music in one chip from 1989. Contemporary ROMs of the time for things like computers were already holding hundreds of kB, but those aren't the sort of thing you find on a cheap novelty christmas product. There's at least roughly 4,400 events stored in that chip.

If you want the sequence for yourself, here it is. You can play it back using this crude python program.